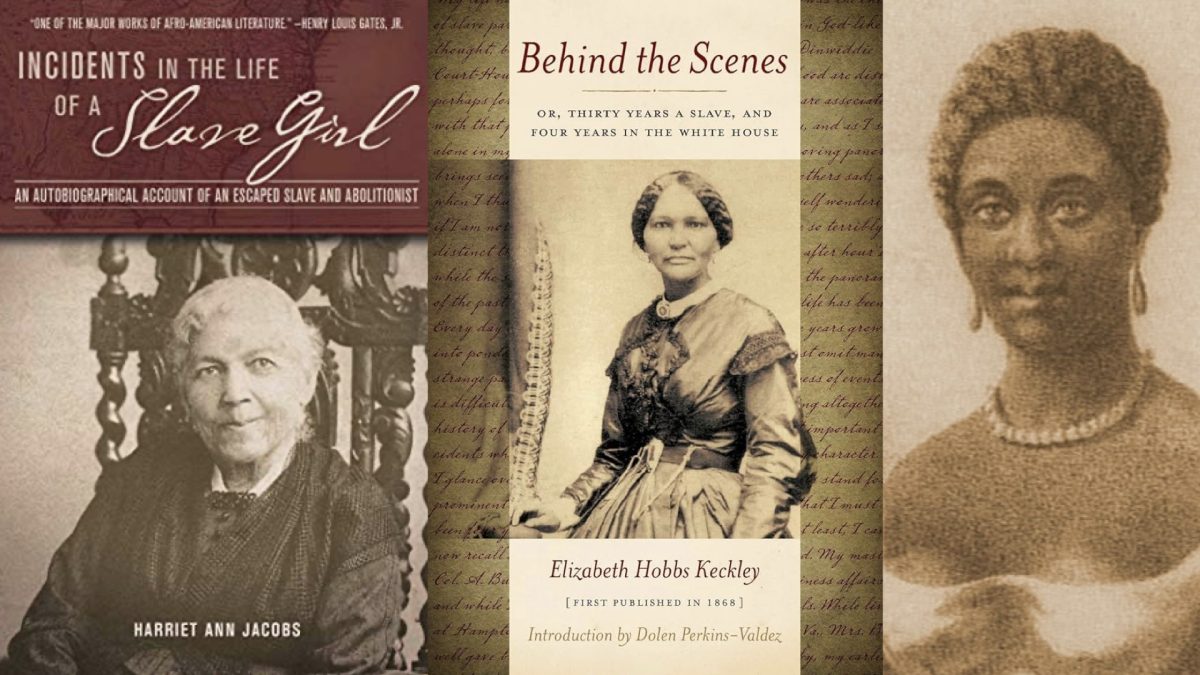

The life of a person who is considered the property of another and is subject to his authority in all things is demeaning and insufferable. Take it from Harriet Jacobs (a.k.a. Linda Brent, pen name), a biracial slave, who hid in her freed grandmother’s small attic for seven years in order to escape her married “owner’s” sexual advances and abuse. He had been pursuing her since she was thirteen years old, alternating his coercion tactics between threats of violence and promises of favorable treatment. His wife, Harriet’s mistress, was well aware of and upset by her husband’s infidelity and impropriety, but she was also considered his property and thereby also at his mercy, so she turned her jealous rage upon Harriet instead. In Harriet’s book, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) she tells of of her despair leading her to seek refuge in the harsh locale of the attic, “…the master, whom I so hated and loathed, who had blighted the prospects of my youth, and made my life a desert, should not, after my long struggle with him, succeed at last in trampling his victim under his feet. I would do any thing, every thing, for the sake of defeating him. What could I do? I thought and thought, till I became desperate, and made a plunge into the abyss.” Harriet also shares her personal observations from her time as a slave girl, “I was twenty-one years in that cage of obscene birds. I can testify, from my own experience and observation, that slavery is a curse to the whites as well as to the blacks. It makes white fathers cruel and sensual; the sons violent and licentious; it contaminates the daughters, and makes the wives wretched. And as for the colored race, it needs an abler pen than mine to describe the extremity of their sufferings, the depth of their degradation. Yet few slaveholders seem to be aware of the widespread moral ruin occasioned by this wicked system… ” Yet, there were several “white slaves” / wives of slaveholders who did, such as British actress Fanny Kemble who married plantation owner Pierce Butler in 1834. The year she spent with him on the Georgia Sea Island plantation her husband inherited drove them to divorce and Fanny became an abolitionist. Also, Mary Boykin Chestnut, a Confederate Lady, who wrote in her journal, “God forgive us, but ours is a monstrous system & wrong & iniquity… like the patriarchs of old, our men live all in one house with their wives & their concubines.”

Even the future of a wife, a dependent, of a generous and important white man was not assured. As Elizabeth Keckley shared in her book, 30 Years a Slave and 4 Years in the White House (1868), during Elizabeth’s time as a dressmaker to Mrs. Lincoln while she was the First Lady, she shared her concern that, “Mr. Lincoln is so generous that he will not save anything from his presidential salary, and I expect that we will leave the White House poorer than when we came into it; and should such be the case, I will have no further need for an expensive wardrobe, and it will need to sell it off.” Two years after being widowed and leaving the White House her situation proved to be as she had foreseen, her income was insufficient to meet her expenses. After struggling to keep up appearances, Mrs Lincoln admitted to Elizabeth in her letter, “I have not the means to meet the expenses of even a first-class boarding-house, and must sell out and secure cheap rooms at some place in the country. It will not be startling news to you, my dear Lizzie, to learn that I must sell a portion of my wardrobe, so as to enable me to live decently,….as I have many costly things which I shall never wear, I might as well turn them into money, and thus add to my income. It is humiliating to be placed in such a position, but, as I am in the position, I must extricate myself as best I can.” This was the outcome the former First Lady which she anticipated years earlier, but was powerless to prevent due solely to her female sex. If only it had been as Mary Wollstonecraft wished in her statement, “I do not wish [women] to have power over men, but over themselves.” Or as Sarah Gimkes declared, “I ask no favor for my sex… All I ask our brethren is, that they will take their feet from off our necks and permit us to stand upright on the ground which God designed us to occupy.” The only reason we are even aware of Mrs. Lincoln’s predicament now is thanks to Elizabeth Keckley sharing it in her book. Within it she also shared her own brutal history as a slave, enduring beatings and sexual assaults before gaining her freedom and working to become a successful dressmaker to the wives of politicians. Nevertheless, there was public outrage over the behind-the-scenes disclosures of her White House friendship with the former first lady which led to public outrage and abruptly ended her career leaving her destitute.

Phillis Wheatley was captured and sold into slavery as a child, then purchased by John Wheatley of Boston. Soon, they recognized Phillis’s intelligence and taught her to read and write along with other studies. In time she became well known locally for her poetry, despite female poets being almost unheard of in this time period. Upon request she wrote the following poem:

To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Dartmouth

. . . No more, America, in mournful strain

Of wrongs, and grievance unredressed complain,

No longer shall thou dread the iron chain,

Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand

Had made, and with it meant to enslave the land. [the colonies]

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Africa’s happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labor in my parent’s breast?

Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

And:

Love of Freedom

In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance; and by the Leave of our modern Egyptians I will assert, that the same Principle lives in us [African Americans].

God grant Deliverance in his own Way and Time, and get him honour upon all those whose Avarice [greed] impels them . . . I desire not for their Hurt, but to convince them [slave owners] of the strange Absurdity of their Conduct whose Words and Actions are so diametrically, opposite. How well the Cry for Liberty, and the reverse Disposition for the exercise of oppressive Power over others agree, —

I humbly think it does not require the Penetration of a Philosopher to determine.